Taming the Two-Headed Beast with Alex Ammar, Editorial Director at Carnegie Hall

On NYC audiences and capital “P” Playbills.

Hello! In this edition of Spectator Sport, I’m speaking with Alex Ammar, Editorial Director at Carnegie Hall. For musicians across the globe, Carnegie Hall represents the culmination of constant practice. For arts editorial professionals, it represents a never-ending marathon. Combining an in-house season and an extensive rental schedule, the venue hosts several hundred shows a year, each with distinct editorial needs and norms, and rarely the same show twice. Hailing from Kansas with a background in vocal performance, Ammar is working to keep this slippery slew of events as stylistically cohesive as possible.

In our conversation, we discussed the best strategies for defining an unfamiliar term (footnote fans, beware), the particular stubbornness of a big-city audience, and the biggest misconception today about how attendees engage with programs. And, if not how, when?

Thank you to Alex for his wonderful insights. Enjoy!

Sarina: What made you want to work in arts editorial?

Alex: I didn’t. I went to school originally as a voice major and dabbled around in other things, including conducting and journalism. I really was going in the direction of record labels and producing and that sort of thing, so I worked at labels for a while. I enjoyed the writing and editing portion of things, and the job at Carnegie Hall came up. At the time, I was not working in the arts or in music or anything — all luxury consumer brand-type stuff, and I wanted to get back towards music.

I’ve been here going on 18 years now. I always joke that I absolutely hated music history in college. Karma is coming to bite me in the ass now, because here I am in this position that puts a premium on having at least a working knowledge of music history.

What does the day-to-day look like for you?

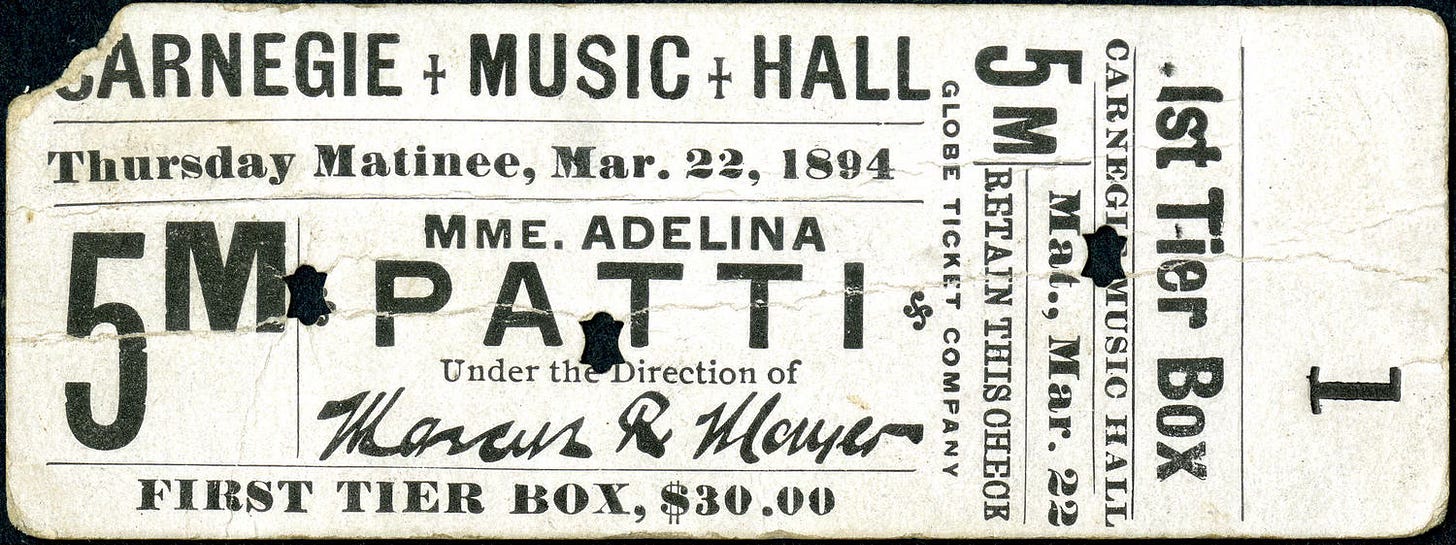

Carnegie Hall is basically a two-headed beast. So, for Carnegie Hall presentations, there's usually about 150 [programs] give or take each season. The woman who is responsible for the visiting presenter playbills can do anywhere from 100 to 300 in a season, depending on the rental schedule. But, in addition to all of that, there are all the emails, all the ads, all the posters, the curriculum books for the Education Department, both for students and for teachers… The general rule of thumb is that if there is a word on something that is going to be seen by a member of the public, and that word is not part of the Carnegie Hall logo, it needs to go through my team. Stuff falls through the cracks all the time, and I just say to everyone, “Look, keep it moving. Mistakes happen.” There's too much volume to be able to stand by everything to the degree that we can say this is 100% without error. We just need to address those, identify the lessons to be learned from those situations, and move forward. Otherwise, we'll never be able to get caught up again.

So, within that two-headed beast, how do the in-house presentations and the visiting presentations relate from an editorial perspective? And how does Playbill tie into all of this?

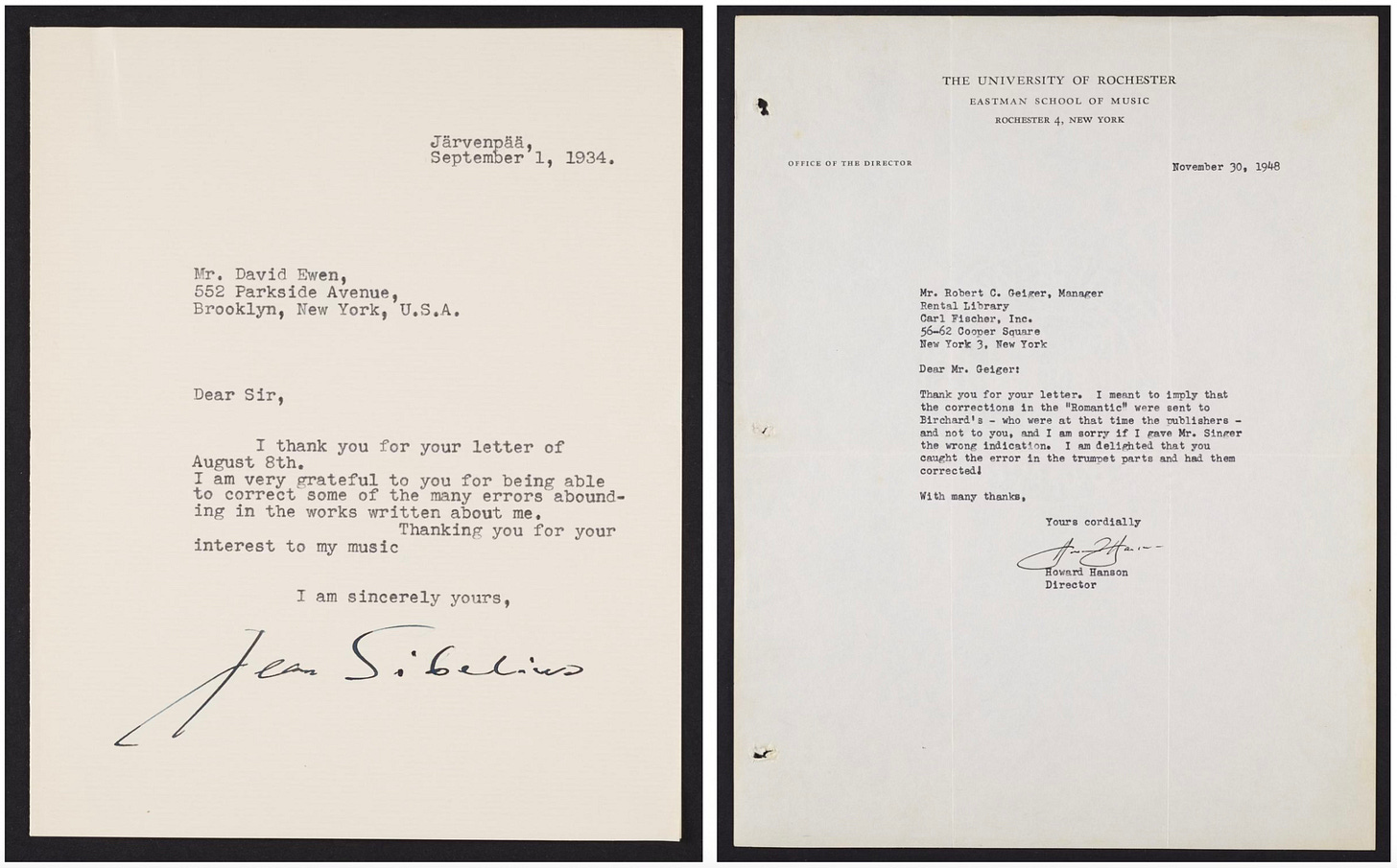

Over the years I've been at Carnegie Hall, their level of involvement has progressively been minimized just because of staffing issues, budget issues — all of that. And so a lot of that work that was previously being handled by Playbill has now come into the Carnegie Hall fold, specifically into my team. What Playbill was doing, which was a very, very imperfect science, was basically taking everything that a visiting presenter wanted to put into their program and essentially shoehorning it into a template, but it was not a very well-executed or regimented template. There was very much a visual disconnect. There was a Carnegie Hall visual presentation of the printed program, and then there was a rental presentation, which was not the same. As we have assumed more of those responsibilities from Playbill, we have tried to unify that a bit more, because, when you're walking down 7th Avenue and you see all the three sheet posters, you visually can tell if something’s being presented by Carnegie Hall because there's a huge Carnegie Hall logo on it. At the end of the day, for an event at Carnegie Hall, you're not identifying the event by who's producing it. You're identifying it as being at Carnegie Hall.

It became cumbersome for Playbill because, you know, we are not their only constituent group. We’re probably their most problematic in many ways, just because of the volume and because of the different types of events that we have. We're not like The Met[ropolitan Opera], where there's an opera or a production that is being seen ten times in a two-month period. We are one night only — at most, we are maybe two nights of the same content.

All of which is to say, Playbill is still our publisher of record; they are still printing everything. We are just doing a lot of the design and editing work for them now. We are mindful that we want to present a unified front at Carnegie Hall and therefore should carry some level of formality and accuracy, but we also have to be mindful that these rental constituents are paying a lot of money to rent the hall. If they want to include something in their program, we have to make compromises. Just because we wouldn't necessarily say or do something in one of our programs doesn't mean that we can dictate to them that they can't do it in theirs as long as it's not offensive, inaccurate, or problematic.

If you're working in a non-repertory theatre, the sheer number of programs that have to be made must be almost unthinkable. Also, this is the second time I've spoken to someone in symphony editorial work whose organization is moving away from a kind of “Playbill down” strategy and starting to develop more of an in-house approach to these programs. Why do you think that's happening?

I think that, with the pandemic, people were trying to find ways of bypassing print, because, at the time, there was a real need to not have to physically hand something to someone. The other thing that is probably more unique to Carnegie Hall than it is to other places is that our proximity to Broadway innately means that the majority of the audiences coming into the hall are expecting a Playbill. Not just a program, but a Playbill — a formal Playbill. So that's why you'll see a lot of the New York houses, whether it be The Met or any of the other Lincoln Center constituents, still using Playbill. There are some like BAM (Brooklyn Academy of Music) that self-produce their own; same with Perelman [Performing] Arts Center. They produce their own, but there is an officialness and a sort of “New York stamp of approval” with that Playbill logo. If you don't have that in the city of New York, particularly if you're uptown near the theater district, I think that it sort of starts to lack a little bit of that expected experience that you're there to have.

To what sort of existing knowledge base do you think these audience-facing materials should cater?

We try to present all of the information in a way that casts a net as wide as possible — that will not be intimidating or use inside baseball musicological terms for the novice audience member, but at the same time is not pedantic or speaking down to those audience members who have heard [Gustav] Mahler five bajillion times.

At the end of the day, you kind of have to realize that you're never going to be able to make everyone happy, and that if someone really is that much of an expert in something, they're not gonna read your program notes anyway. The notes are really there as a study aid of sorts for people who want to learn more, but the experts are not going to pay attention. And, if they do, what I have found is that their reason for paying attention is to find errors.

What are the common mistakes people make when writing about classical music?

People don't want to be told what to listen for. They don't want to have a play-by-play. I think what is probably most interesting and most helpful is to learn more about the context in which a piece was written. What was going on in the world at the time? How did this piece essentially respond to that?

I'm really curious about what you've mentioned, because I think this play-by-play is what people have come to expect when they think of program notes. As in, “What are the top three things I need to know in order to ‘get’ what I'm listening to?”

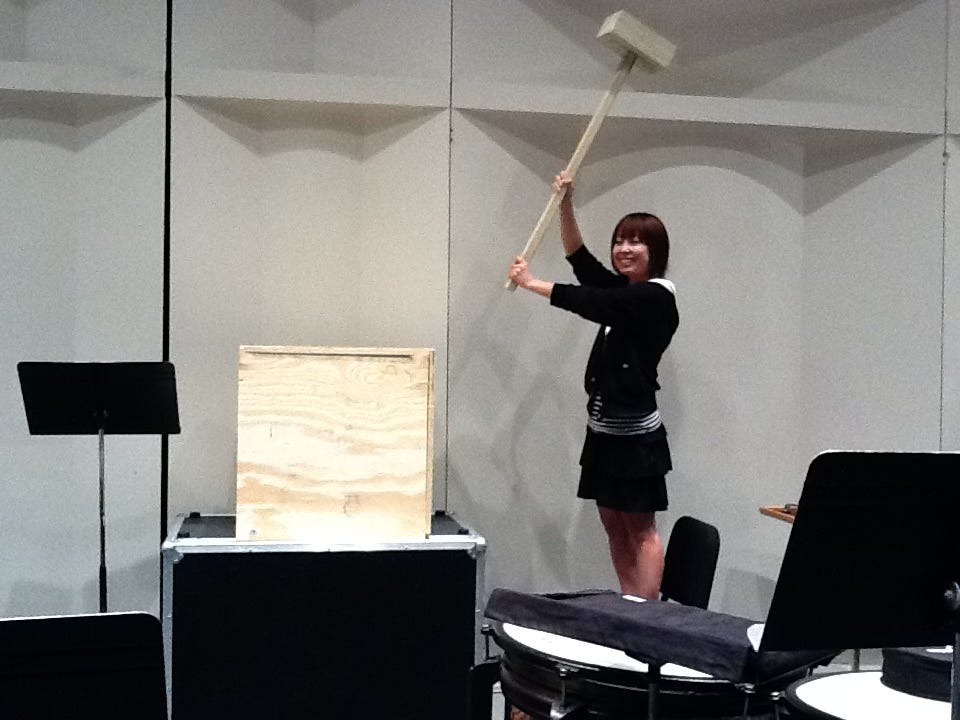

If someone really doesn't have much fluency in the art form, they're not gonna know what you're talking about. If you say, “Listen for the timpani,” that's gonna mean nothing to them. If you say, “Listen for the big boom,” that might be a little more approachable for them, but it's really not of great importance or insight into the work or the composer or anything. I mean, the Mahler hammer blows at the end [of Symphony No. 6]; that's one thing. But most pieces don't have those sort of hallmark-type sounds that you really can draw out.

The one thing that's sort of ignored in the conversation about program notes that I’ve found is, “When are people engaging with them?” They're written from the standpoint of someone in the concert hall reading them at the same time as a performance, and that's usually not the case. And you don't want the audience to read during the concert, because then they miss the whole point of the concert itself.

We will publish our program notes on the website about a week before each of the events. What often happens is you're given your playbill, you go to your seat, the concert starts, and you don't pay attention. Oftentimes, people don't actually read the program notes to whatever degree they're reading them — at least in New York — until after the concert, when they're on the subway on their way home and can sit down and actually read it with some sort of focus. If you're giving someone a play-by-play, and they're reading it after the fact, you've missed the opportunity to give them anything of use.

Wow, I have literally never thought about how much the timing of when you read the program note affects what should be in the program note, but you're absolutely right. That play-by-play doesn't work, especially if you're going to hold onto the program note and consult it later.

I am going to throw out some ideas, and I'd like to get your opinions on them. First off, defining terms in a program note. Parentheticals or footnotes — where do you stand?

Parentheticals.

Really?

Absolutely. It breaks the rhythm of the written word when you're having to go find the footnote and then contextualize the footnote, as opposed to a parenthetical, where it's all seamlessly packaged and provided to you in a much more user-friendly format. In my opinion, you should not feel as though you're reading a textbook or some sort of scholarly article. There are plenty of people who would disagree and who would say it has to be from a scholarly perspective, but that's part of the problem with classical music, in my opinion. If you're presenting it from that angle, no wonder people aren't interested in it, you know?

I see what you're saying. With a footnote, it's almost like the page is sorting you into a lower echelon of readers. As if to say, “We're using this term and we would rather just keep talking about it, but if you need the definition…”

What do you think about first-person program notes?

I knew you were gonna ask that! Yeah, I think it depends on who's writing it and the piece. If, for example, it's a composer statement, and they're writing about their process, and it's clear that it's from their perspective, then it absolutely should be first person. For a lot of our annotators, what they'll do is, if they want to insert the composer's voice, particularly for someone who's been gone for decades or centuries, they will quote them and use their words to enhance the thought process or the message or context of the note.

I'm not averse to the first person, but it has to be used as a tool with a purpose. It can't just be used because we're trying to be conversational. To me, that sounds a little more Mickey Mouse, and it's more like what we do for some of the younger kids' curriculum books. You know, “I’m Bach, and I wrote blah blah blah for the harpsichord, which came before what you all consider the piano today….” That kind of thing.

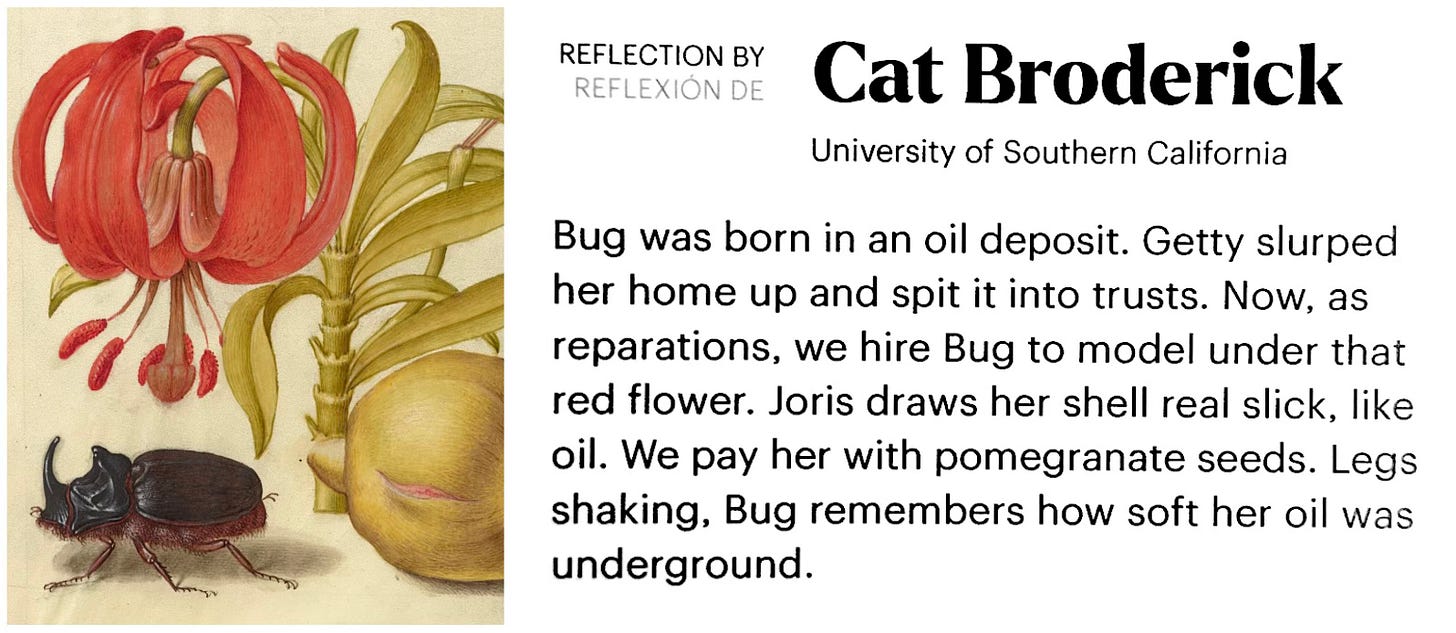

I see what you’re saying, although I’m not sure I agree. I was at the Getty several months ago, and they were putting on an exhibit all about medieval manuscripts. With each manuscript, they had a curatorial note from interns, spanning from poetry to personal stories. But, from what I understand, you don't feel that that sort of anecdotal information is appropriate in a program note. Is that it?

I think it depends on who's writing it. The example that you gave to me would be more of an artistic statement. So, let's say that the conductor wanted to include an artistic statement: “I chose this because blah blah blah.” That makes sense. But, for a third party who seemingly is removed from the overall sort of presentation of the program, to me, it just seems as though it's adding another voice to something that doesn't necessarily have relevance. A note being an artistic statement — whether it be from the performers, the composer, whoever — that's one thing that we always like to have. But I don't like reading program notes where it is an annotator who is removed from that process completely and is trying to invoke their own experience, because it doesn't necessarily mirror or reflect what the intention of the artists was. It's just a third-person voice being added to the mix. Does that make sense?

It does, though I do have this romantic idea of programs that quote from children who have come to see, for example, “The Magic Flute.”

I totally get what you’re saying. That's different because it's giving you another perspective that is not purporting to be any sort of authority.

Right, I see.

When we're commissioning a writer to write something and we're presenting them as someone who has working knowledge, who is articulate and able to convey different thoughts and ideas in a meaningful way, they're coming at it almost like a professor. And you don't want the professor to tell you, “Well, you have to read this this way.”

That’s an example of just a difference of vocabulary, you know? Program notes are one thing, an artistic statement is another, and while they both in print are very similar and look the same, the functions of the two are very different. You can have an artistic statement without a program note. You can have a program note without an artistic statement. The two combined provide very different entry points into the music.

To throw another thing at you: games in programs. What do you think of crosswords? Word searches?

I don't like them. I love activities like that, but the concert hall is not the place unless it is an event or a program or a performance that uses that as part of the experience. We used to do these printed activities for the kids to partake in, but the performers were leading those exercises and those activities, so the kids were engaged and learning from each other and the musicians at the same time, having their own exploratory experience in the concert hall. It's the same thing as having that step-by-step explanation of what to listen for. You're probably not going to be able to pay attention to what's on the printed page because the lights are down. You're missing the point of the performance; it's a distraction.

How about stickers and programs?

For what purpose?

As a memento. As in, “I went to the symphony. I got this sticker.”

If there's a reason for it, yeah. If it's just a gimmick, I would rather receive a sticker separate from the program, only because the program to me is kind of… I'm probably an antiquated geek when it comes to this, but I keep all my programs. If it's a sticker that I want to save and that's part of the overall experience, yeah, I would keep it inside the program. But, if it's just like a “I went to Carnegie Hall” kind of thing, I don't know. I could go either way on that.

It's an interesting point, Sarina, because think about it this way: in our playbills, there's the monthly component of the playbill and then there's the daily component that is specific to the concert. If you have the sticker and you can use that sticker almost as a bookmark of sorts, then it has purpose. It's a moment. There's additional value. Particularly in a place as sophisticated as New York can be, I think some people would sort of frown upon it. But if there's an additional reason for its inclusion, I think people would be all for it.

What do you make of digital programs that you scan a QR code to access?

Oh, God. That is a loaded conversation. As part of the whole COVID experiment, that was one of the things that we really looked into, particularly as the landscape and financial circumstances with Playbill changed and evolved over the years, part of and separate from COVID. I think that everyone would love to find a way to have digital programs. I don't think that it's possible, at least not without an industry-wide educational push to move the audience's expectations. I think audiences — again, particularly in New York — are too familiar and expect to receive a Playbill.

We've had soloists or musicians on stage who have literally stopped the performance because someone has their phone out and on. Not that they're talking on it or texting, but they can just see the glare of the screen. And there's all sorts of accessibility considerations. Until there's a way to streamline that and make that a part of the concert-going experience in an unobtrusive way, I just don't see it happening.

This could be something that is more unique to New York than other places, but there’s a social media value in showing your playbill. Pardon the expression, but the number of friends I have on Facebook or wherever who are showing this playbill with the stage in the background…. I mean, like, OK, you're going to see “Gypsy” with Audra McDonald. Good for you, but how many of those playbills do I need to see in front of that stage? There is inherent value in that, particularly for something like a Broadway show, where you see that someone went to see it, they raved about it, and you can actually go see that same show at a different time. Carnegie Hall doesn't necessarily make that available, but there's something about that physical space that I think people are still drawn to.

Well said. I'm now going to say a few sentences, and I'm interested to hear your opinions on them. The first is “The best program note writer is the one who knows the most about the music.”

No. I think the best program note writer is the one who is curious and provides context that might not be as obvious, that opens a window into something else, more curiosity for the reader or the audience. It's not presented as the end-all be-all, but it's provided as an entrée or a guide for more.

We have a very finite amount of words that we can print, so we're not going to be able to present a comprehensive sort of assessment of where this work fits within their larger canon or even specific details about various nuances within each of the movements.

Another: “Audience members who know more about the historical context or analytical significance of a piece will get more out of it.”

I think that's a slippery slope. That feeds into the stereotype that the classical arts are inaccessible and not for everyone, that they innately speak down to people who may not know as much about a specific subject. We have a lot of people who come to our shows who know a lot about various things, and like to flex those muscles. Kudos to them, but that doesn't mean that their opinion of something is any more accurate than someone else's articulately presented perspective.

“The orchestra hall is an intimidating place.”

I agree. We've done marketing studies about this several times during my tenure at Carnegie Hall. It is because it’s not presentational in the way that theater is. There are fewer visual aspects for the audience to respond to or to have a working knowledge of. It really more specifically requires an aural know-how and familiarity in some people. I don't think it's difficult once you've made that leap. I don't think it's difficult to appreciate.

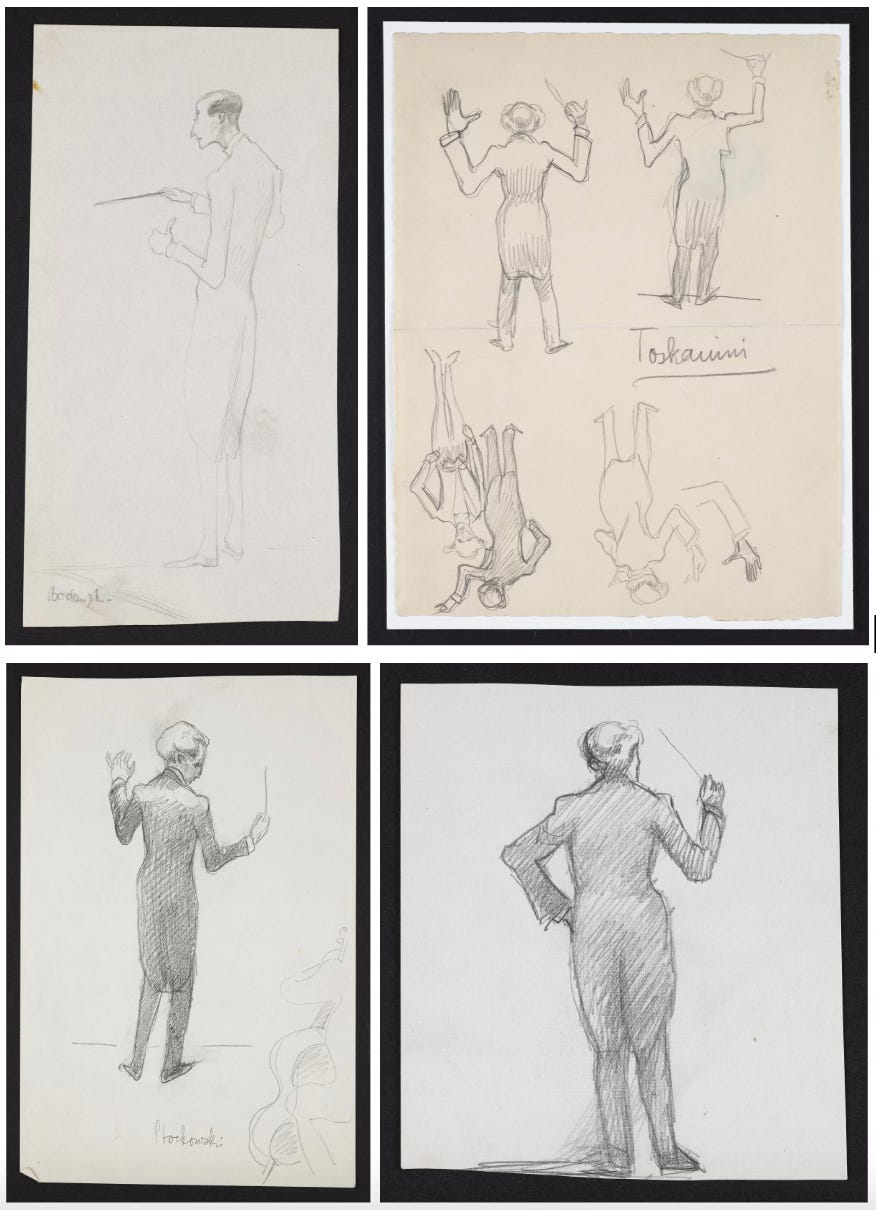

I could see why a novice arts goer would prefer going to a ballet over an orchestra. At the ballet, you have costumes. You often have scenery. There's visual interaction between the dancers, whereas the visual interactions between the instrument groups within an orchestra aren't quite as noticeable if you're not looking in the right space at the right time. I mean, basically, most of the visuals of the orchestra are just the backside of the conductor. And however flamboyant or crazy they are in their gestures, there's only so much of a conductor's backside, frankly, that you can see.

Carnegie Hall is the prime example of this. From the street, we are not an inviting venue. We have this cavernous lobby that is kind of dark and echoes a lot. You don't see the hall or anything. There's not some interesting street-level storefront or anything like that. We don't have this massive fountain gathering space that Lincoln Center has, you know?

In these uninviting spaces, what role does the program play?

A tool for understanding. A contextual enhancement of the experience.

Broadly, what do you wish were different about the way arts organizations spoke to audiences?

That's a really tough question. It's not a one-size-fits-all for all types of programs.

In the arts in general, there's so much importance and weight put on press quotes, using that as the metric for artistic merit. While that can help to introduce someone to something or someone new, I've seen bios and marketing copy where it's just a string of press quotes. Another after another after another. It's kind of like, where's the point of view? The justification through press quotes starts to become hollow.

What project in your time at Carnegie Hall are you most proud of?

I'd say the overall improvement of our program materials — visual organization, consistency, and content. I hope that those would be hallmarks of my tenure at Carnegie Hall.

It's been a slow-moving process. I think that identifying where there were issues, identifying who the audience was, and what made most sense, and digging deeper into the way that people engage with program materials all filtered into that. There was an appetite to make those changes from the top down. Sometimes the audiences were a little hesitant to come along for the ride. At this point, I think that they've all made the leap with us. Or at least they're still coming, whether or not they're reading what we give them.

What do you think would surprise people most about your work?

I think that people would expect there to be a high level of detail, but I think that they would be surprised at how high that level of detail has to be. The big “Oh shit” moment is always when the New York Times reviewer calls out the annotator for something that was either incorrect or that they disagree with. That’s the level of scrutiny that you have to be prepared for.

What advice do you have for someone who wants to work in your field?

Don't discount your music history classes. Probably the big piece of advice is don't get hung up on what you perceive to be the pathway in. There are many, many different paths into this line of work. You can be someone who has specialized in musicology and has no journalism background. You can be someone who has a design background and can write well. I think the main thing is you have to be curious and you have to strive for accuracy, whatever that means to you. It can be a very roundabout journey. Use all of the tools that you've amassed and all of the skills that you've cultivated to set yourself up for success, but what is successful for me is not going to be successful for you, and what I bring to the table is not necessarily what you bring to the table.

That was great advice — heartening advice. It was advice that felt good to hear.

I mean, if you had asked me when I was in college or in high school what I wanted to do, this was not it. First of all, I didn't know that there was such a job like this, and I never would have thought that I would have been qualified. For a while, even when I first got the job, I felt kind of like a fraud. I hated music history, as I said, and here I am in this position where I'm having to basically convey some level of music history to people. That wasn't my forte. My forte was in visual design, articulate speech patterns, and communicating in the written word to a vast audience. That's what I brought to the table. I really had to work at that — keep my main skills at the forefront and make sure those didn't suffer as I was trying to bring everything else up to speed. You know, it's a balancing act as always.

I believe it.

A Postscript

After speaking with Alex, I went to see my mom and grandfather play ten three-minute entr’actes for a local retirement community’s sixty-five-minute showcase. Though the Potomac Green Playmakers have almost no internet presence, and though the actors and attendees have almost no commute, the community center still made a point to bring in capital “P” Playbills, bright yellow box and all. Copyright 2025.

Thank you for reading this edition of Spectator Sport. I hope you will spectate here again.